Woodgraining or faux bois is a delicate art requiring an understanding of nature as well as the tools and techniques to attain convincing faux wood finishes. Among other decorative finishes such as faux marbleizing, trompe l’oeil, and grisaille, woodgraining intends to simulate another form. When properly executed, the results are so convincing, onlookers marvel at the beauty of the simulated form versus the hand of the artist.

While the art of faux finishes had been in practice since the Roman ear, the Victorian Era saw the peak of the practice, especially woodgraining. Woodgraining and faux finishes became practice and developed popularity for numerous reasons. First, out of necessity. The cost to faux finish an architectural detail is significantly less than the genuine substance. Second, woodgraining allows for a controllable consistency throughout a given interior.

The artist must refrain from becoming “artistic” when woodgraining. A painterly hand in the practice of woodgraining is unbecoming of the trade. There is no place for artistic license in woodgraining. Such gaudiness is akin to costume jewelry and will not convey the desired sophistication of precious woods. To suggest anything more than the purity of the wood at hand is beyond the intention of the technique. Let nature be the inspiration and the guide.

Without taking liberties with the markings, knots and veins of the wood, the craftsman can produce consistent simulations of the most beautiful natural cut of the wood. By painting the wood finish, the craftsman develops perfection foreign to nature.

In order for woodgraining to be successful, the paint must be employed within the construction of interior in the same manner genuine wood would be used. Decoration must “arise from, and should properly be attendant upon, Architecture” (Grammar of Ornament, Owen Jones). This is especially true when simulating architectural elements.

Technique

Faux finishes in general can be applied over any substrate including glass, Sheetrock, plaster, woods, composition boards, metal, or plastic, so long as the substrate has been properly prepared and primed.

Proficient drawing skills are necessary but do not define a good woodgrainer. Knowing what to add next to the composition and when to stop are the difficult tasks required of the craftsman. Concrete understanding of the subject matter, is developed over years of study. Students and apprentices of woodgraining are required to sketch the grains of numerous woods in order to gain the valued understanding of nature required to simulate the grain with success. Once the individual can produce a sketch from memory, painting techniques begin come into play.

A good craftsman rarely works from a reference. His/her understanding of the wood should be so great that the brush becomes an extension of the arm to create the image ingrained in the mind’s eye.

Process

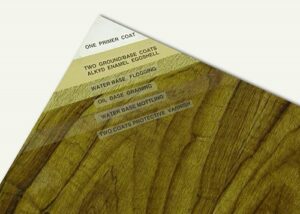

Woodgraining and marbleizing is rarely achieved in one step. It is usually a process of two to four applications. The techniques and materials used in woodgraining are similar to that of marbleizing. Most woods and marbles are a 2-3 step process. Sometimes an additional 4th step is necessary.

Basic Steps

-

- The first step in woodgraining is a ground or base coat of paint, specific in color to the species of wood being imitated.

- A water scumble is then applied over the ground coat. While still wet, the scumble is manipulated with a horse hair brush called a flogger which is design for the purpose of simulating pores in the wood. The process is called flogging because the brush is thrashed against the wet scumble in an upward motion.

- Once dry, the next step is to apply the oil scumble. The colored pigment is then picked up from the palette board, rubbed into the medium and manipulated to represent the markings. These markings are then softened and blended with a badger hair softening brush.

- The next step is the application of a glaze which changes the overall tone of the wood and adds more depth and translucency.

Tools of the Trade

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Flogger, 2 different sizes.

- Glazing Brush

- Lamb’s Tongue

- Fan Overgrainer

- Softening or Badger Brush

- Tooth Brush or Spalter, four pronged.

- Stippling Brush

- Narrow Stippling Brush

- Rubber Combs, 2 different patterns.

- Check Rollers, 2 different sizes.

- Rubber Combs, rollers

- Steel Combs, 2 different sizes.

- Overgrainers, 2 different sizes.

- Mottlers, 3 different sizes.

- Pencil Overgrainers, 2 different sizes.

- Burlap

- Sponge

-

-

-

-

-

-

If woodgraining is done properly and appropriate to the architectural elements, the result is both convincing and effective. However, if the work is poorly executed and looks very painterly, it can appear kitsch.

With these processes having been briefly explained, it must be noted that simply following instructions does not properly attain such a craft. An accomplished grainer has a dexterity of hand and a profound understanding of nature that allows for confident brush strokes.

The Aesthetic Morality Argument

The Scientific American published an article in 1846 on decorative painting and the art of faux finishes stating that the practice of such techniques had not “been so much in vogue as at the present. Imitations or pretended imitations of oak, maple, mahogany or marble, may be seen on three-fourths of the doors of houses in the cities, besides wainscoting, chimney pieces and furniture.” Another guidebook listed imitation woods are the prize of the craftsman. To be successful in “executing a good specimen of graining; and the imitation of the graining of expensive and high-class woods is still the favorite method of embellishing woodwork that is subjected to hard wear (Pamela Hemenway Simpson, Cheap, Quick, & Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials, 1870-1930).”

Such praise and suggestions are rarely met without opposition. John Ruskin among others, marked faux finishes yet another lie in an ever declining society. Ruskin despised deception in art claiming that “there is no meaner occupation for the human mind than the imitation of stains and striae of wood and marble (John Ruskin, Stones of Venice).” Similarly, Sir George Gilbert Scott further paralleled the advancements and alternatives of the day to the “decline of truthfulness and the prevalence of deceit (Sir George Gilbert Scott, Remarks on Secular & Domestic Architecture).”

A practical craftsman from Manchester wrote a letter in the paper in response to the arguments of the elite art critics of the day. He questions the lie that the critics accuse the woodgrainer of, fore if the craftsman never impersonated a mason or carpenter and produces a painted product at the request of the owner, what is the crime? He argues that there is now crime but truly honest work with the use of honest paint, varnish and craftsmanship (Pamela Hemenway Simpson, Cheap, Quick, & Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials, 1870-1930).

Owen Jones also defends the use of faux finishes so long as the practice remains within the proper bounds of the architecture. Just as any object might be ornamented to be more beautiful than its original form, so might simple pine appear like mahogany within the proper context.

Critiques of days past and present thoroughly ponder the “aesthetic morality” regarding the deception of faux finishes. Though few will dispute the technique and craftsmanship of the trade, many prefer the true material to the imitations. The most thoughtful response to such opinions is answered with the simple fact that nature is the inspiration for all art. Woodgraining is an art derived to flatter and decipher the beauty in the world around us; an illusion rather than a deception.