Historic restoration calls for an in-depth study of the building’s history, often through a historic structures report, which typically includes various types of analysis. One such analysis is a historic paint analysis, also called a historic finishes investigation, which is a process by which layers of paint are removed to reveal past color schemes, decorative campaigns, and finishes.

The paint investigation aims to discover a list of information that can be leveraged by the structure’s owner and architect in order to understand what kind of restoration, preservation, or conservation work may be appropriate. Namely, this information includes the original colors, their makeup, and the existence of decorative stenciling, woodgraining or other decorative elements.

But what, exactly, happens during a historic paint analysis?

The Process

A historic paint investigations should consist of four steps through which an interior design is studied, catalogued, analyzed, and summarized. This includes: Conducting archival research, on-site investigation (including the gathering of samples), laboratory analysis, and the compilation of a report and interpretation. We explore each of these steps below.

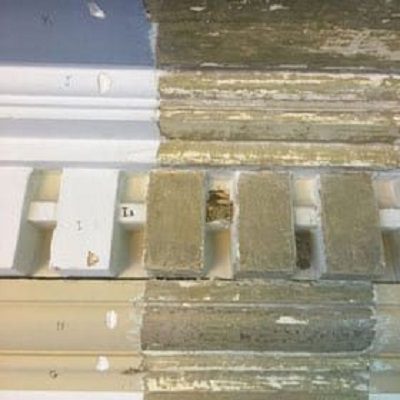

Window exposure at wainscot

1. Archival Research

Archival research is an essential first step to an analysis before samples or onsite investigations take place. The information gathered during archival research guides where samples should be taken and provides direction to where exposures, or paint reveals, should be performed within a space.

The designer takes the form of archaeologist when digging into the history of the paint on a wall, ceiling, capital etc. Like archaeologists, research begins long before stepping on site, with the completion of archival research.

Reading historical annals and flipping through magazines of the day not only sheds light on the building itself, but also on the community that interacted with the structure, and the purpose for which it was built. By better understanding the time as well as the interior design of the structure, the designer is able to develop a cohesive idea of the room as it once was.

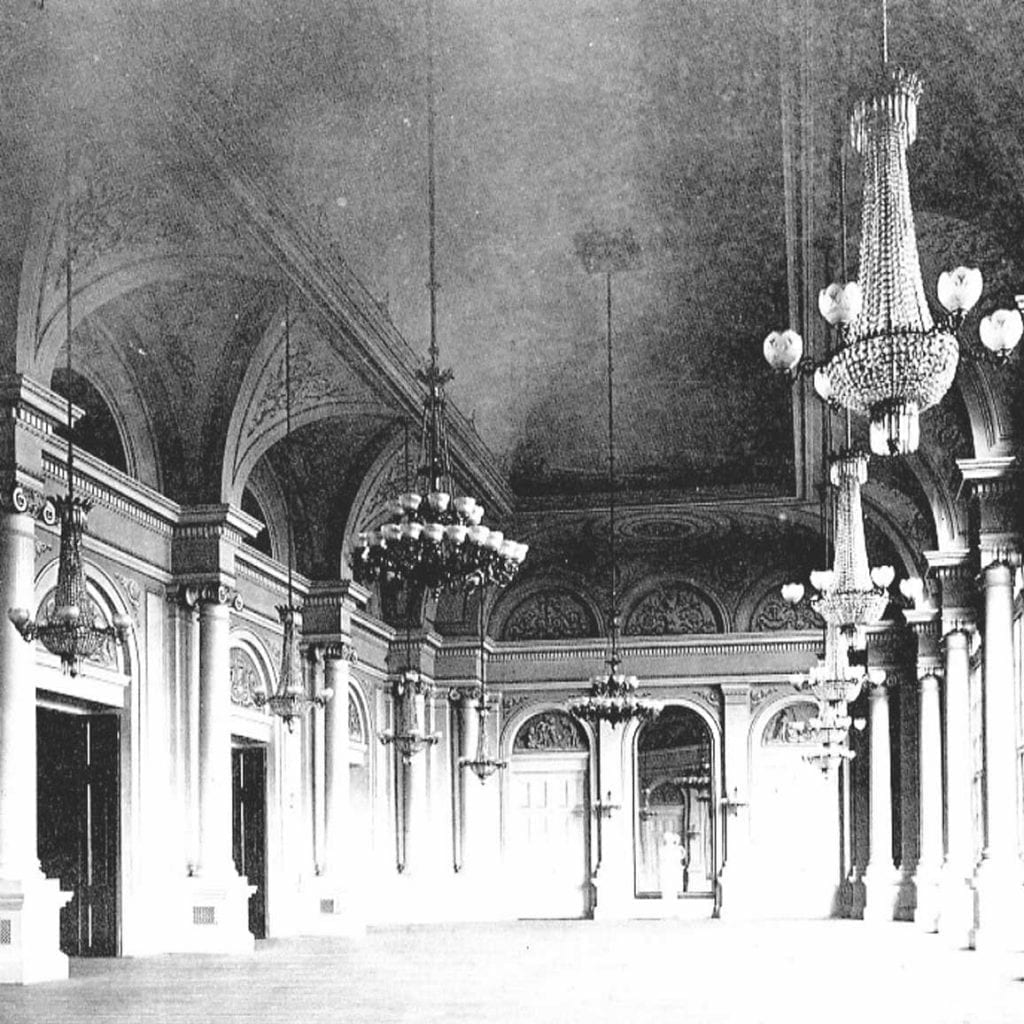

In addition to written sources, historic photographs are integral to the research process for obvious reasons.

Microscopy Analysis

2. Onsite: Exposures & Samples

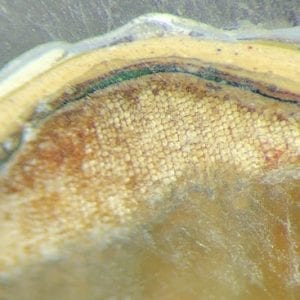

Onsite work involved in a historic paint investigation includes paint exposures and collection of paint samples (or, sometimes, simply the collection of paint samples). An exposure is an archival dig that uses mechanical and/or chemical methods and materials to remove layers of overpaint to reveal the significant campaign.

While laboratory analysis allows us to see the number of layers of overpaint and the significant color, in situ investigation reveals the hand of the original artist such has freehand details, stenciling, or faux finishes such as faux bois (woodgraining) or faux marbres (marblizing). The process of an exposure requires a knowledge of the components of the original paint as well as the overpaint in order to successfully reveal the original campaign without harming the finish.

By carefully stripping away layers of top paint, the original campaigns are revealed or exposed (hence the term “exposure”). Though tedious, this process is extremely rewarding. Experience, as well as the archival research, guides the placement of the exposures. Paint samples from the different areas of the paint exposures and throughout the room are collected for studio analysis at the same time.

If archival research and the intended style of the building reveal that exposures are not necessary because the room was never decoratively painted, the proper approach would be to collect and analyze paint samples rather than perform full exposures.

Full exposure of decorative designs on pilaster.

3. Laboratory Analysis

During field investigations, paint samples are taken from various locations and architectural features. The collected samples are then brought to the lab for scientific analysis. Microscopy analysis reveals the paint stratigraphy and chromochronology as well as the composition of the paint. By manipulating the paint chips under a microscope, the different layers of paint, varnish, and even dirt can be viewed, analyzed, and understood.

The number of samples taken may vary depending on the complexity of the architecture and decorative campaign features. The key to a successful microscopy analysis is in the sample. Size may vary but it’s important to take samples that are intact from the current paint layer through the substrate.

The samples must be studied under either natural north light or polarized artificial light to simulate natural light. Natural light is integral to analyzing the samples accurately without disruptions from glares or direct sunlight. When each layer is properly identified and catalogued, the paint colors are matched to the Munsell color system.

4. Report & Interpretation

The findings from the archival research, on site exposures, and each paint sample, are then organized into a final report with recommendations for the future. Perhaps the most important aspect of a paint analysis, the interpretation considers all aspects of the finishes investigation to provide the documentation required for restoration or conservation.

The report is twofold, as it is a summary and a suggestion. Going forward in the restoration process, this report is referenced for historic accuracy of the decorative design. Being that it compiles the history of the original design, make-up of the different materials and uses written documents, photographs and scientific research to back up the decisions made, this report becomes an important referred to both on the project and in the future. If the interior is to be restored, such a report is integral to the accurate advancement and historic integrity of the project.

Historic Paint Investigation In Progress

Opening Windows to the Past

It is said that the eyes are windows to the soul; paint exposures provide a window for the eyes to the soul of the past.

A paint investigation is essential to historic restoration; without such a study, the designs throughout the interior will most certainly be inconsistent with the original scheme and no longer of historic value. Aside from this process being crucial to the primary stages of restoration, exposures and laboratory analysis encourage a curiosity and excitement that captivates individuals and propels the project forward.

The history of once was will always be mysterious, when the windows into the original design are unveiled we are not only enlightened with this information but also, for a moment, as if peering into the looking glass, we are transported into a parallel past and the history of the building.